Although the Ewe (pronounced “Ev-ay”) are not as well known outside Ghana as the Asante they also weave many of the cloths known worldwide as kente. In fact many collectors regards Ewe textiles as the highest expression of African weaving artistry. Ewe people live around the Volta delta area of south eastern Ghana and across the international border in Togo. According to their local histories some groups reached their homeland in the seventeenth century after a series of migrations from the east, passing through the town of Notse in Togo. Others, around the more northern weaving town of Kpetoe claim an Akan origin from an area towards the coast near Accra. Unlike the Asante they were never a unified political entity with a powerful court, being ruled instead by numerous village chiefs and shrine priests. Perhaps as a consequence of this lack of a centralised royal authority imposing common standards Ewe weaving is far more diverse than that of the Asante. Although they do supply important regalia to local chiefs, Ewe weavers work primarily for sale through markets and to fill orders from important local men and women. Today Ewe weavers are concentrated around two towns, Kpetoe and Agbozume, with the latter the site of a large cloth market which draws buyers from throughout Ghana as well as neighbouring countries.

Ewe weavers utilise an almost identical form of the narrow-strip loom to that of the Asante, and there is considerable evidence to suggest mutual influence between the weavers of the two traditions, as might be expected from the long history of contacts, both through trade and conquest between their peoples. However Ewe weaving has also been influenced by and exercised an influence on other neighbouring peoples, including the Fon of the Benin Republic and most recently the Yoruba of Nigeria.

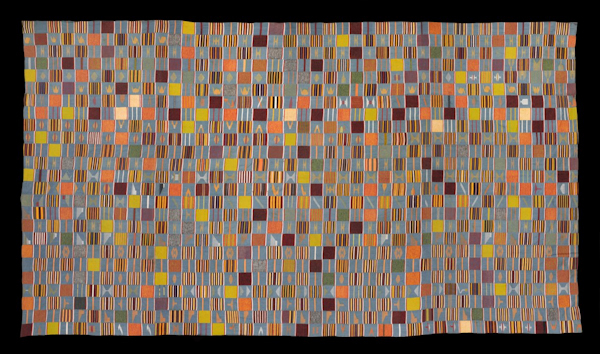

One particularly interesting and distinctive type of Ewe cloth, sometimes called adanudo, features a rich variety of weft float inlaid pictures, often on a plain silk, rayon, or cotton background. Among the subjects depicted on these cloths are animals such as cows, sheep and horses, human figures, ceremonial stools, hats, trees and flowers, and household objects such as dining forks. More recent examples are often quite realistic, and at least since the 1940s some of the cloths have included written texts. The Ewe weavers also produced many cloths where, as with Asante kente, the main design feature is symmetrically arranged blocks of weft float designs and weft faced stripes across the strips. However despite their superficial similarity, these cloths can generally be distinguished from Asante weaving by the inclusion of figurative designs of the type described above, and by the use of a technique which involves plying together two colours of weft thread before weaving a band, creating a kind of speckled effect. Ewe weavers also produced more simple but still striking cloths using just indigo blue and white stripes and checks, perhaps the legacy of older weaving styles practised before they came into contact with the Asante.

Further Reading:

Sadly there is as yet no in-depth publication that gets to grips with the amazing diversity of Ewe weaving. However all the books listed below are useful.

Adler,P. & Barnard,N. (1992). African Majesty. Text is mostly drawn from Lamb but great photos of a major collection.

Ahiagble,G. & Meyer, L. (1988) Master Weaver from Ghana – brief but charming children’s book with great photos.

Kraamer, Malika “Ghanaian interweaving in the nineteenth century: a new perspective on Ewe and Asante textile history.” in African Arts Winter 2006

Lamb, V. (1975) West African Weaving

Ross, D. (1988) Wrapped in Pride – mostly about Asante but some info on Ewe and interesting pictures.

Posnansky,M. “Traditional Cloth from the Ewe Heartland” in History, design and Craft in West African Strip-Woven Cloth (Smithsonian 1988) – looks at blue and white cloths from Notse, Togo.